The Briefing Note:

The "Way" was a societal contagion, not a private opinion. In the Acts 2020 Project, Lens 5 examines the high-friction intersection where the early Church met the established Roman order. This was not a clash of religious ideas, but a systemic disruption of local economies, imperial politics, and social hierarchies. We analyze the forces that sought to quarantine the movement—and the radical "Dynamics of Acceptance" that allowed it to thrive in the face of total opposition.

Forensic Fixed Points:

The Sovereign Evidence

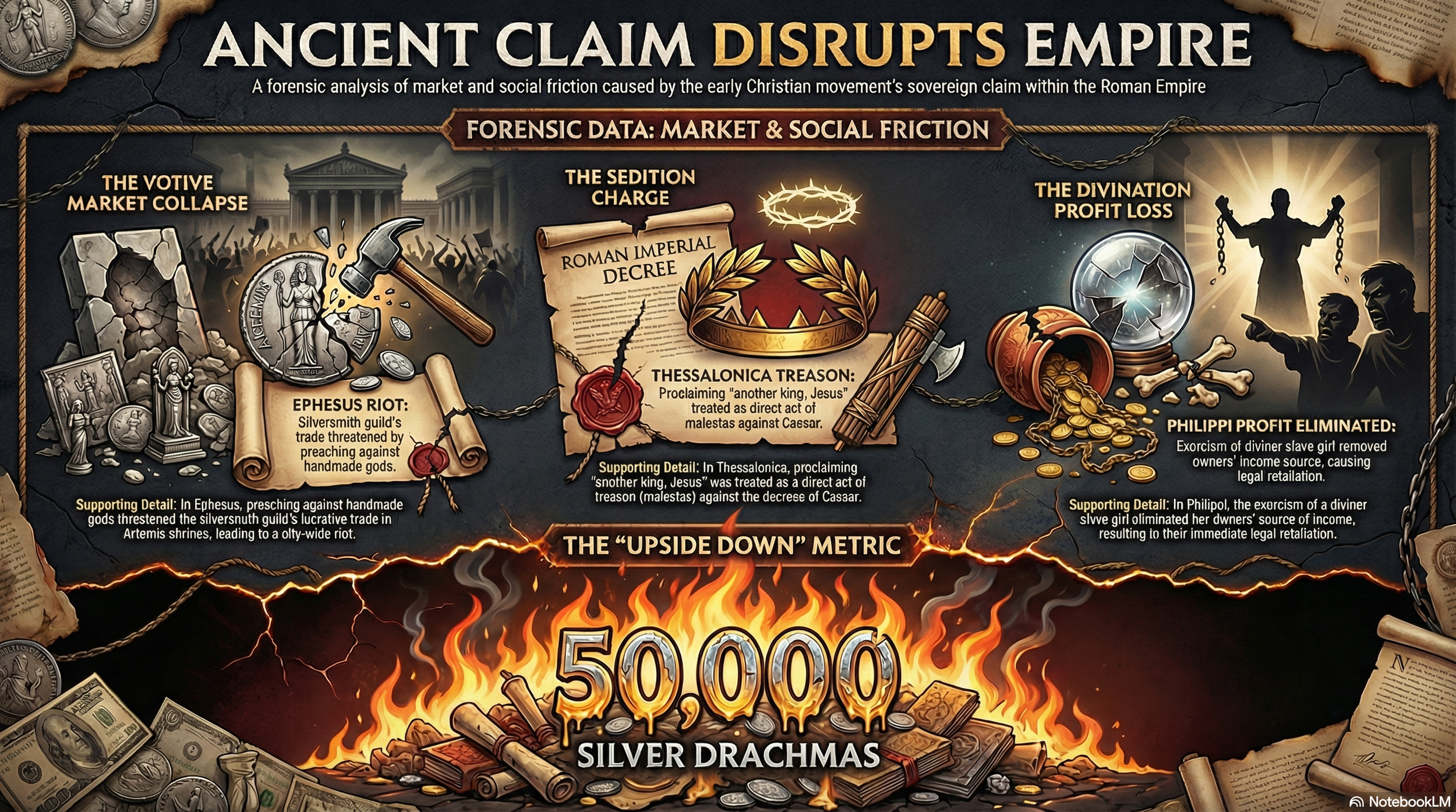

The Artemisian Bank Crisis: In Ephesus, the movement threatened the regional liquidity of the Temple of Artemis, which functioned as the "Bank of Asia." The riot was a desperate market intervention to save a pilgrimage-dependent economy.

The Sedition of "Another King": The charge of "turning the world upside down" in Thessalonica was a formal legal accusation of maiestas (treason). Proclaiming a rival King challenged the core of the Pax Romana.

The Agape Table Subversion: The movement gained high-status acceptance by dismantling Roman social hierarchy. At the Christian table, ethnic disgust and class boundaries were dissolved, creating a "transgressive" social community.

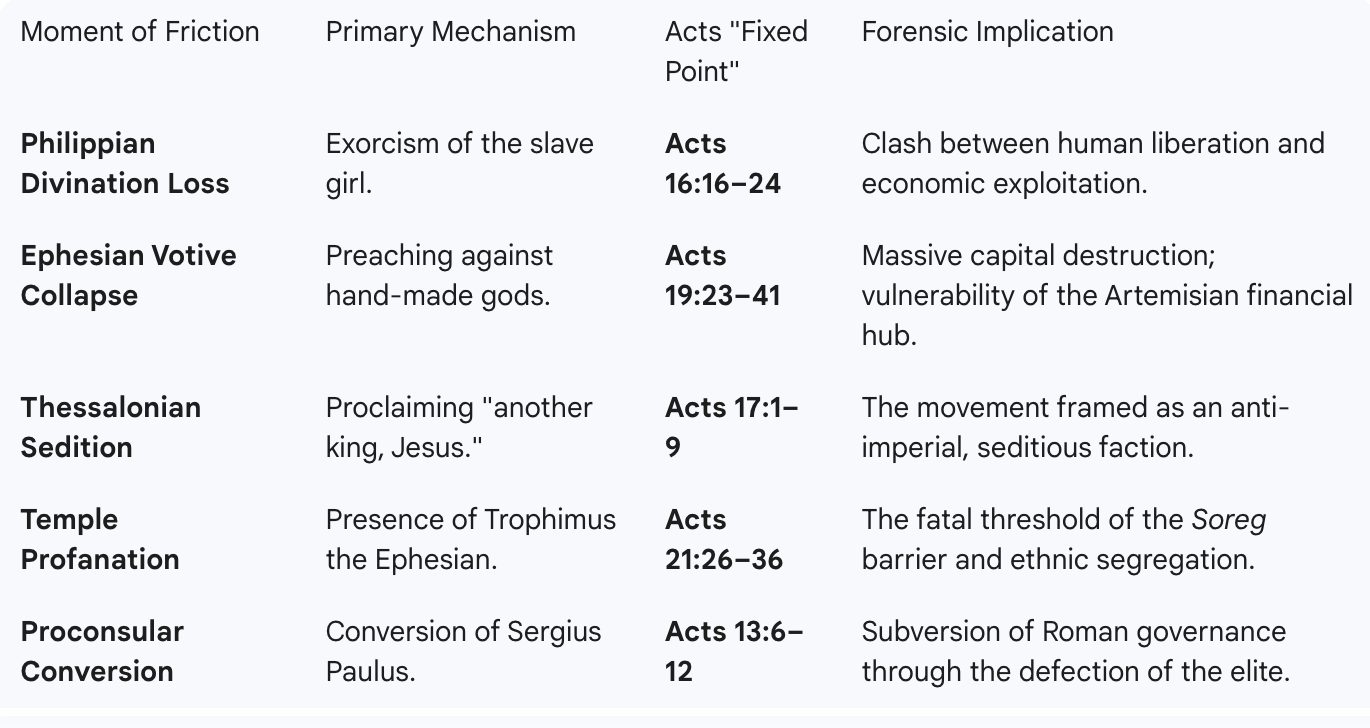

Forensic Data Table: Market & Social Friction

Case File Questions:

To "Cross-Examine the Evidence" in the Hub, use these questions:

The Economic Impact: Why did a spiritual message cause a macro-economic "run on the bank" in the province of Asia?

The Treason Charge: How did the proclamation of a heavenly King function as a political threat to Caesar?

The Social Contagion: Why were "women of the first families" and Roman officials drawn to a movement that upended their social status?

The "Upside Down" Metric: How did a multi-ethnic, cross-class community dismantle the traditional hierarchies of the 1st-century world?