The Briefing Note:

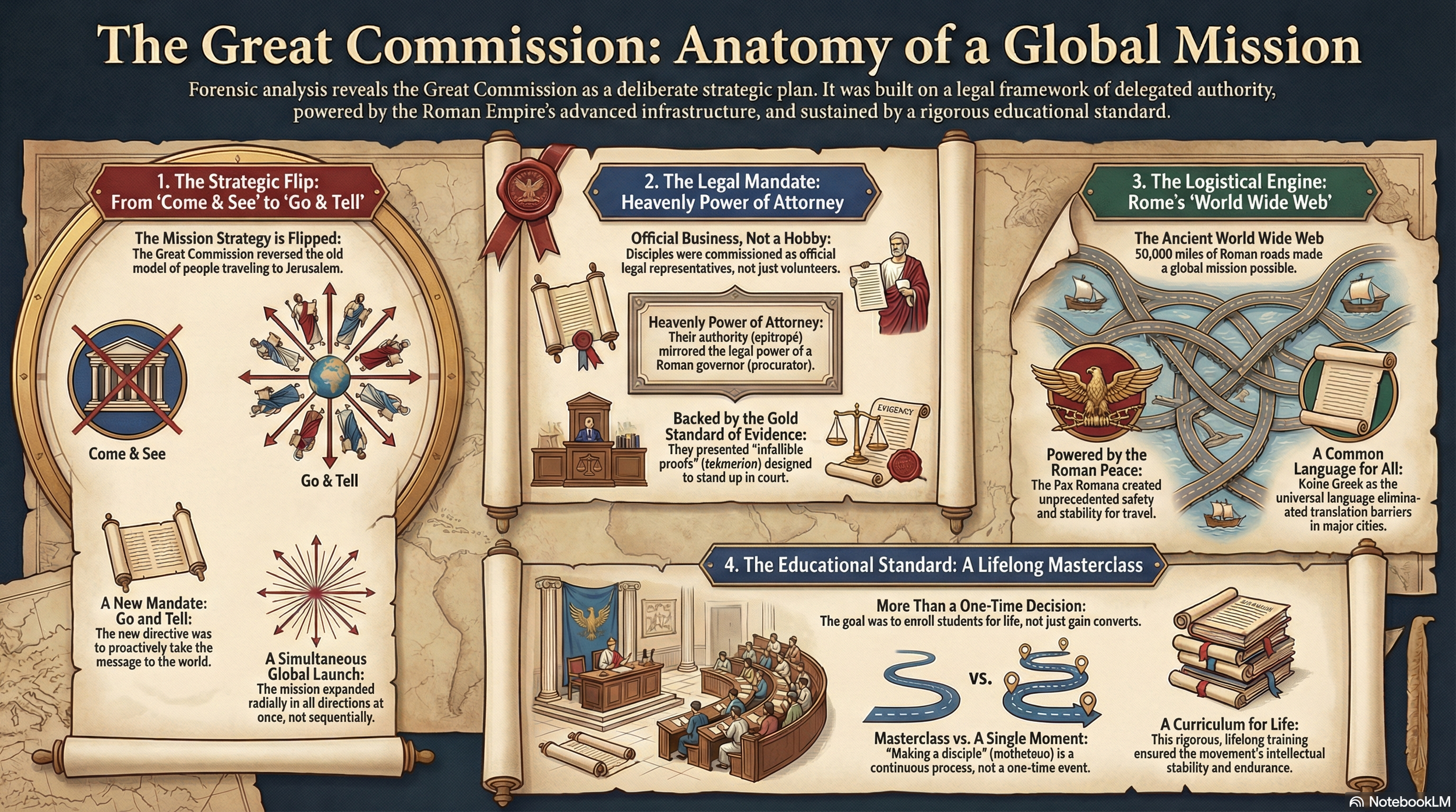

The Great Commission is the project’s Operational Mandate. It transitions the mission from a localized Galilean ministry to a global, "Centrifugal" expansion. Driven by the supreme authority of the Risen Christ and anchored in the "infallible proofs" (v. 3) of the Resurrection, this mandate defines the Church’s strategic objective: to make disciples of all nations. It is not a suggestion, but a formal commissioning that provides the "Unbroken Thread" for every action recorded in the Book of Acts.

Lens 1 — The Great Commission

The Strategic Architecture of the Global Mission

The Executive Mandate: More Than a Suggestion

The Great Commission is the foundational "Business Case" for the Book of Acts. As any leader would recognize, any global expansion requires a clear mandate from the highest authority. Jesus provides this in Matthew 28:18–20 and Acts 1:8. This is not a religious suggestion; it is a Strategic Directive backed by what Jesus calls all authority in heaven and on earth (Matthew 28:18). In the first-century Roman context, this was a formal commissioning (epitropé)—a delegation of power that empowered the disciples to act as legal agents of the King.

When Luke writes that Jesus began to do and teach (Acts 1:1), he is signaling that the Great Commission is the continuing executive action of the Risen Christ. The Church does not act independently; it is the authorized arm of a Kingdom that is expanding across geographical and ethnic borders. This mandate defines the Church’s raison d'être (reason for being). If the Church is not "commissioned," it is merely a social club. In Acts, we see this mandate transition from a localized Galilean ministry to a Spirit-empowered global movement.

The Forensic Standard of Proof (Tekmerion)

A critical component of this Lens is the standard of evidence required to launch the mission. Jesus did not send His disciples out based on a "feeling." He presented Himself alive by many infallible proofs (v. 3). This Greek term, tekmerion, is the "Gold Standard" of evidence used by physicians for diagnosis and lawyers for trial.

The Great Commission is built on this forensic foundation. For the mission to move from Jerusalem to Rome, the messengers had to be absolutely certain of the facts. Luke, the physician-historian, meticulously records these "briefings" over a 40-day period. This was not just a time of fellowship; it was a high-level training seminar where Jesus prepared His "executive team" to witness to a skeptical world. This forensic certainty is what turned a group of frightened disciples into fearless witnesses (martyres) who would eventually turn the Roman Empire upside down.

The Strategic Pivot: Centripetal to Centrifugal

The Acts 2020 Project highlights a seismic shift in mission strategy within this Lens. Historically, the Old Testament model was "Centripetal"—nations were expected to come to Jerusalem to see God’s glory. The Great Commission flips this model to "Centrifugal"—the Church is commanded to go out into the world.

The geographic blueprint in Acts 1:8 (Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria, and the ends of the earth) is the "Programmatic Outline" of the entire book. It is a ripple effect. However, it is not just a slow, concentric expansion; it is often a simultaneous launch propelled by the "friction" of persecution. For example, the martyrdom of Stephen in Acts 7 and the subsequent persecution in Acts 8 served as the catalyst that forced the Gospel out of Jerusalem and into Samaria. From a business perspective, this is "forced market expansion." What the enemy intended for destruction, God used as a distribution network.

The Teaching Standard: Making Disciples (Matheteuo)

A common misconception is that the Great Commission is only about "conversions." However, the core Greek verb in Matthew 28:19 is matheteuo—to "make disciples." This is a didactic (teaching) mandate. It involves the meticulous, long-term process of teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you (Matthew 28:20).

This aligns perfectly with Luke’s forensic goal of "Exact Truth" (asphaleia). The Commission requires the teacher to prove the reliability of the account to the student. In Acts, we see this in Paul’s "reasoning" in the synagogues and Peter’s "explanation" of the scriptures. This is a rigorous intellectual and spiritual process. It is about building a foundation of truth that can withstand the intellectual scrutiny of the Greeks and the religious traditions of the Jews. The Great Commission is a call to a high-density, evidence-based education in the life and Lordship of Jesus Christ.

Empowerment: The Holy Spirit as the Administrator

The Great Commission is humanly impossible without the Holy Spirit’s Role. Jesus explicitly commanded the disciples to wait until they received power (dynamis) from on high (Luke 24:49). This dynamis is the "Forensic Energy" of the mission.

At Pentecost (Acts 2:1–4), the mission is ignited. The Spirit provides the boldness to speak, the miracles to validate the message, and the linguistic ability to cross cultural barriers. As the Great Commission unfolds, we see the Spirit acting as the "Chief Operating Officer" of the mission—forbidding Paul from entering certain regions and explicitly calling him to Macedonia (Acts 16:6–10). This Lens reminds us that the Commission is a Trinitarian effort: commanded by the Father, anchored in the Son, and executed through the Spirit.

The Response: A Divided Verdict

Whenever the Great Commission is executed, it provokes a response. This is the Lens of Christianity Accepted & Opposed. We see 3,000 saved in one day (Acts 2:41), but we also see riots in Ephesus (Acts 19) and legal trials in Caesarea.

The Great Commission is a "disruptive technology" in the first-century religious and political marketplace. It challenges the status quo of the Roman Emperor and the Jewish Sanhedrin. For the 2026 reader, this is a vital lesson: the success of the Commission is not measured by universal popularity, but by the faithful proclamation of the truth. Resistance is not a sign of failure; it is often a sign that the message is hitting its mark.

The Eschatological Trajectory: To the Ends of the Earth

Finally, the Great Commission has an "End Goal." It is moving toward the return of Christ. The angels in Acts 1:11 promise that Jesus will return in the same way He left. This provides the "Urgency of the Mission."

The "ends of the earth" (Acts 1:8) is not just a distance on a map; it is a spiritual finish line. This Lens connects the history of Acts to the hope of the future. It reminds us that we are part of an "Unbroken Thread" that started on a mountain in Galilee and continues through our own neighborhoods, workplaces, and global mission efforts. We are carrying the same "briefcase" of evidence that Peter and Paul carried, with the same authority and the same promise of Christ's presence: I am with you always, even to the end of the age (Matthew 28:20).